A Post-Apocalyptic Writer in Chernobyl

I’d just gotten back to my Kiev apartment after exploring the nuclear ghost city of Chernobyl and Pripyat all day. I remember undressing and looking at my clothes and shoes in a pile, thinking, “I can’t possibly keep these can I?” After walking through all that radioactive dust? I read differing opinions online, late the night before, when I couldn’t fall asleep. I had been up all night awaiting my early morning bus to Pripyat. In the end, I did keep my sneakers. I had only brought two pairs of shoes to Europe, and I figured a good rinsing would get that dust off.

I was first introduced to Chernobyl through documentaries and video games. Many post-apocalyptic worlds emulated—or downright copied—the overgrown, crumbling skeleton of a city known as Pripyat. Call of Duty 4 had a level based on the city. The game Stalker sets you up to wander the irradiated meadows of northern Ukraine, within the danger zone, carrying a Geiger counter.

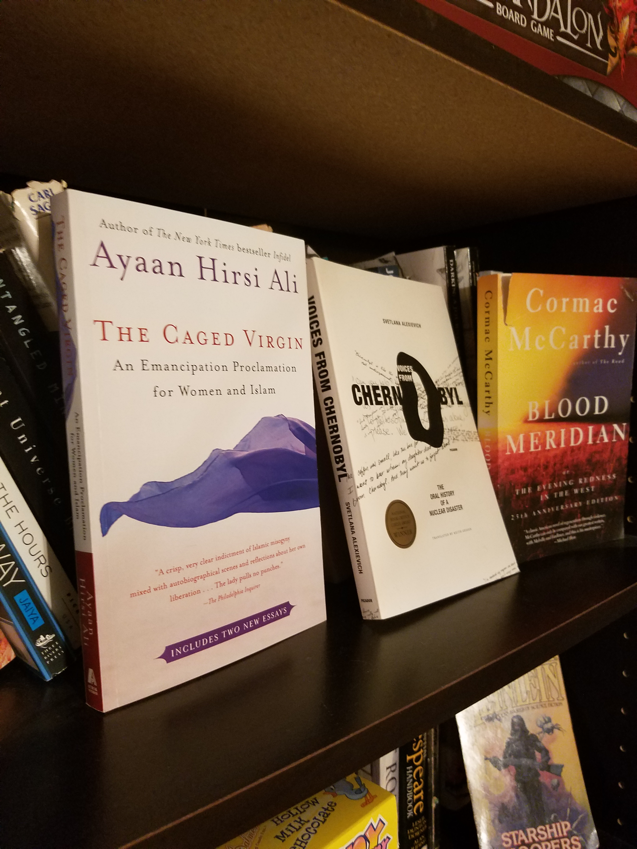

Then, in 2012, I read Voices from Chernobyl. This is the book that took my simple interest in a cool and haunting dystopian-fiction-writer’s fantasy environment and complicated it. What I mean is, I never personally connected with the tragedy, or understood that my whole trip to walk the streets of the abandoned city could be viewed as something awful: dark tourism, the commodification of the epicenters of heartbreaking historical tragedies.

Reading the diaries of the residents of Pripyat in Voices from Chernobyl, I was brought to tears. I remember I had been reading it at my desk at school once, at the end of a long day of teaching, and one of my coworkers came into my room. She immediately asked if I was okay. Was there something wrong? Yes, but I couldn’t explain it. It was a horrible feeling given me by the pages. A closeness with the tragedy only literature has the power to offer.

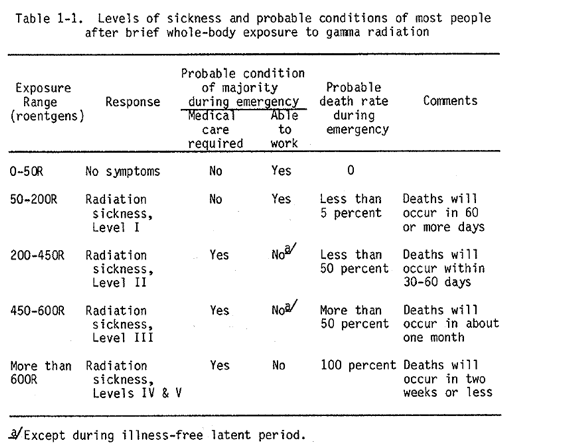

Reading the diaries of the families ripped apart on April 26th, 1986—how quietly the disaster came and changed everything—was devastating. The streets lined with what looked like snow, but was really radioactive ash. How firefighters who fought the radioactive blaze—right at the heart of reactor 4—came home to their families, appearing unscathed, only to die a slow and agonizing death over the following weeks, at the hand of something entirely invisible and untreatable. Reaching points where heroes would have to be quarantined from their own loved ones. Babies that would later be stillborn because husbands and wives couldn’t obey the order—the order of no, you can’t visit with your husband as he dies and his skin slides off each time he’s moved around on the hospital bed, because he’s gotten too high a dose of roentgens.

It was one of the worst disasters in human history, and the worst nuclear disaster. The “official” death toll listed is almost laughable once you begin doing research. Look up the disaster and you’ll find 31 deaths cited. Dig a little deeper and you’ll uncover details about how the USSR didn’t even let the rest of the world know about the meltdown, so bent were they on outside appearances of strength and perfection. It took the radioactive clouds floating over Sweden for someone to figure out something was wrong, and then for the USSR to admit it needed help. Toxic clouds floated almost across the whole planet. The disaster was so costly, both in human life and resources, that it’s sometimes listed as a prime catalyst for the fall of the USSR. Dig a little deeper, and you’ll find some sources citing 10,000 lives lost. Keep digging, and some sources estimate the cost in lives at six-figures, when you take into account the people who would die from cancer caused by the exposure long after the initial blast in reactor 4.

For better or worse, I’ve always been fascinated by ghost towns, and this is the most famous ghost town. It’s a ghost city actually, formerly home to 50,000 citizens of the CCCP. The entire city of Pripyat was built for the sole purpose of housing the workers and families of the power plant. Immediately after the disaster, the rest of the city wasn’t told of the immediate danger It was covered up. A few days later, however, the authorities ordered that everyone would have to leave—in just a handful of hours, all 50,000 people were to gather up whatever they could carry from their apartments and evacuate, never to come back. I can’t begin to imagine…

When I first landed in Ukraine, I stayed for a couple nights at a hostel near the river Dnieper. I met an Aussie at check-in and we got along well. He was there to stay for 6 months, and he said he’d gotten a job teaching English simply on the credential of being a native speaker. I told him I was staying for a couple weeks to get to know the city. When I told him I was booking a tour to Chernobyl, he gave me the same response I had been getting from just about everyone: “Why would you want to go there?”

No one is allowed to go to Chernobyl on their own, as it is restricted, and you must reserve a trip at least a week in advance. I later found out that with the right connections, or a bribe, getting in on your own is possible, especially if you’re not a tourist. It’s only in the last couple years that the tourism industry has really kicked in, capitalizing on this dark tourism site, as it has other places of historical tragedy, such as Auschwitz in Poland, the country I had been in before flying to Ukraine.

I explained to those who thought I was stupid or crazy that I was really fascinated by Pripyat, and tried to articulate solid reasons for my trip. It’s not enough that I write post-apocalyptic fiction, and thinking of—let alone seeing—human-vacated environments in my head is an essential task. I tried to explain that the book about Chernobyl I’d read had touched me, that I’d long been interested in the story. I’ve also always been interested in the region in general. My ancestry is one quarter Slavic, and my great grandfather traveled to America from Ukraine. Still, even from locals, the look I received was something like “you’re nuts.” When I would push and ask why, trying to deflect from having to offer a rationale for the apparent risk everyone thought I was taking, I would get a warning about the radiation. But from others, mostly the Kiev locals, I would get a truer mix of the real reason: Along with being radioactive still, it’s such a sad place. It lives in the recent memory of their nation—the disaster happened in the 1986, not very far in the past, and still close enough that the people I was having conversations with had family members affected by the disaster.

Hollywood has capitalized on the creepiness of the city, making The Chernobyl Diaries (a film that lost its potential after about 15 minutes). The video game industry has taken inspiration too, and shown us Pripyat-like landscapes in The Last of Us (maybe the best game I’ve ever played, where you control a character inside an explorable world-become-Chernobyl). Even The Road, one of my favorite post-apocalyptic books, takes cues—consciously or not—from the images of the nuclear ghost town in Northern Ukraine.

Some of Pripyat’s famous images I’d seen over and over—the rusted old bumper cars, the Ferris Wheel, the apartment high rises. These structures seemed larger than life to me, iconic, and I couldn’t imagine what it would feel like to finally see them in person. The city had been about to open an amusement park for the children. They never made the opening date—Reactor 4 exploded on April 26th, and the park was set to open on May 1st, just 5 days later.

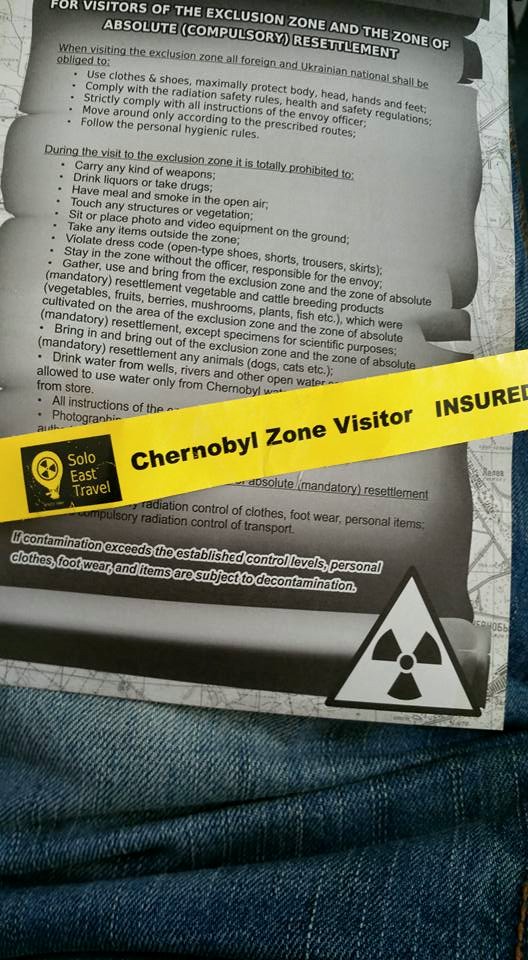

Leaving for Chernobyl, I followed the instructions I was given for clothing. Wear a long-sleeved shirt and long pants. I threw on jeans and a thin Henley. I had barely slept the night before. While my roommate Pavo, who roomed with me in various European cities that summer, slept in the room next to me, I escaped at dawn on no sleep, walking up the main drag, Kreschatik, toward Independence Square, to the hotel where the bus would pick us up. Independence Square was lined with photographs of the fallen—the many who had died just a year prior in the Euromaidan, or Ukrainian revolution of 2014.

We all got on board the old bus and were handed warning flyers and wristbands to wear. Then the driver took off. The bus played a documentary of the disaster on a TV screen (the same one I had watched on Youtube during my insomnia the night before) while we bumped along for the next hour or so. Eventually we reached a checkpoint and had to stop. There was a map on the side of the road that showed the exclusion zones and colored certain areas off-limits, or restricted to time limits and certain personnel. Armed military guards inspected us and put us through a scanner and then, after twenty minutes, we were off.

When we got to the city of Chernobyl, which is not as close to reactor 4 (the site of the meltdown) as Pripyat is, I was shocked to learn that people are still living there, despite government mandates that they leave. Apparently the risk is pretty low now, and some people simply had nowhere to go.

We wandered around the town of Chernobyl and looked at some of the robots that had been used to go inside the reactor and handle dangerous debris. They looked like miniature tanks, with spindly arms that looked like they could be used in Battlebots. There was a sense of suspense as we got closer to the actual ghost city, surveying these robots had been sent into the heart of the radioactive inferno some 28 years prior.

When we continued on, everyone got out to take a picture of the Now Entering Pripyat sign. As a post-apocalyptic junkie for so many years, I never thought I’d be standing there, looking at it. I’d seen it represented in other places—movies, games—so many times, and here I was. Sometimes you feel so far from home, and in a place where people warn you not to go, that you wonder if you’ll ever get back home. In that moment, and for the rest of the trip, I didn’t feel that way at all. I wanted time to stop.

We finally reached the city after going through the irradiated forest (known as The Red Forest for the color, which changed due to the massive absorption of radiation). There was talk on the bus about the local animals, many of them altered genetically due to their toxic environment. My fatigue vanished as the rain started and the bus jerked to a stop. We had come to our first stop in the abandoned city, an old school building.

I almost expected everything to be wide open, like in some of the pictures of Chernobyl, but this old school was heavily surrounded by forest. You couldn’t even see the apartment building next door without traveling through an overgrown thicket of trees and bramble.

The first thing I noticed upon entering the school was how dusty it was. I had no idea if the dust was radioactive, but I assumed it wasn’t, otherwise how could they let us in here? The crew must know where the radioactive hot spots are.

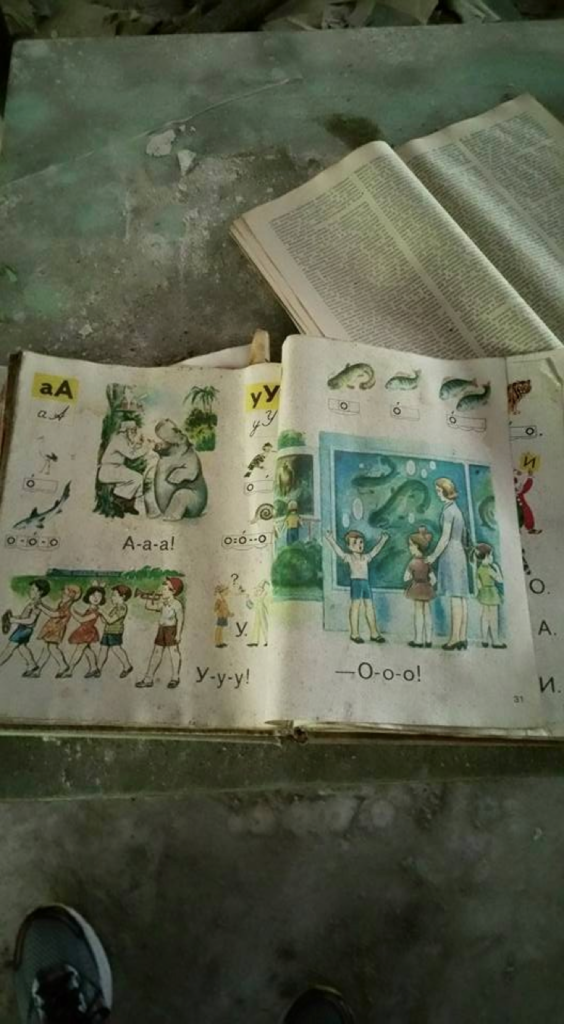

Every room was torn apart. The paint was peeling, there were gasmasks on the floor, old school books scattered across children’s desks. Basic math written on the wall and bulletin boards half-disintegrated with the Russian writing still visible. I had learned the Cyrillic alphabet enough to make out some of the writing—school, math, Russian.

Everything felt unreal. You feel compelled to take picture after picture in a place like that. I did, and so did everyone else. But none of them capture the feeling of walking around. The organization of the tour was very loose—we were told by our Ukrainian hosts to be back at the bus in half an hour. Where can we go? Some asked. We could go anywhere, he said.

It felt like a matter of time before the stairs crumbled and collapsed. Still, I went into each room, the forest literally poking inside through broken windows, and water dripping through the ceiling onto the floor with missing boards that at times felt very weak.

I wish I could have stayed longer but we had to move on. You don’t have enough time to get to every room. Some tours apparently let you stay in the city for 48 hours, but not the one I booked. Just a day trip with a limited number of stops.

We went through an old apartment complex. I saw the bare rooms, the old pamphlets on the ground, sometimes furniture rotting in piles in the corner. Some of the bathrooms were ripped out. Some of them looked eerily in pristine condition, waiting to be used.

When we slogged through the rain back to the bus, I was talking with a friend I’d met on the bus. He asked, “Did you get to the roof?” “Of the school?” I replied.

“No, the apartment.” I told him I hadn’t gotten all the way to the top, because I spent too much time in the school taking pictures. He said on the roof he was able to take a picture of the other apartment buildings, all poking through the canopy of forest. That was one of my regrets. I missed my chance to see out over the field of apartments above.

We continued on to another complex where we got to see the giant pool I’d so often seen in pictures. The stories rose up around it and we climbed the mossy and wet and broken stairs to look down at its depth and imagine it filled up with water. It was hard to comprehend that it had been filled with water, that people had been laughing and splashing here not too long ago. I was shocked when I later looked at side-by-side images of what that pool had once looked like compared with what it had become. It had been so beautiful.

We continued on, getting limited amounts of time to explore each new place. As the bus rattled along a canal, we could see the reactors come into view, then slip out of view. We’re heading to the reactor, said the voice at the front of the bus.

Before long we exited the bus in a parking lot. There, right in front of us, was the nuclear reactor. The tour operator held out his Geiger counter next to the famous monument to the nuclear site.

He told us we were just 400 meters from the reactor and we can’t stay here long at all. Then his Geiger counter started beeping. He told us the normal radiation level, and then showed us how high his device had risen.

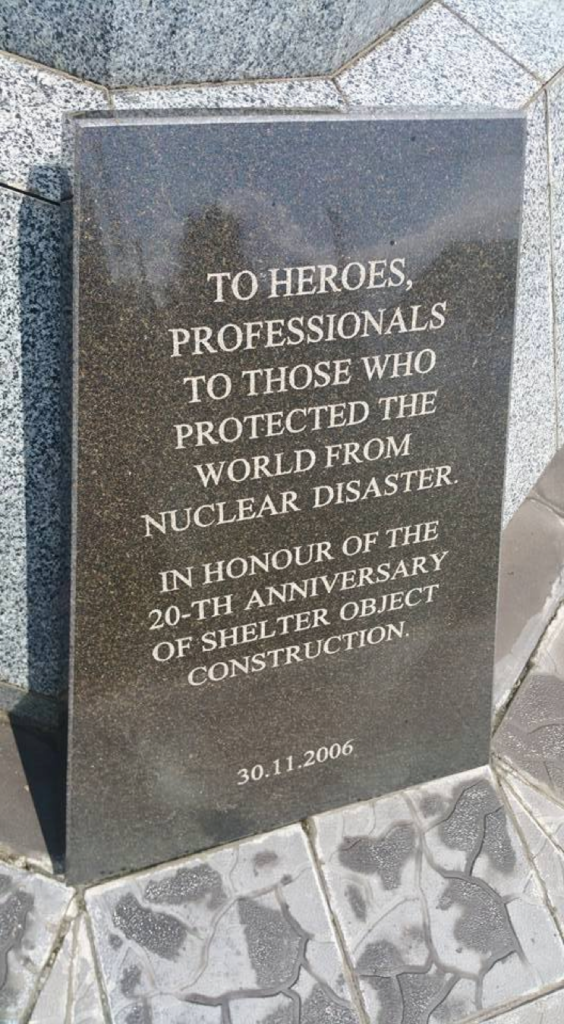

It was creepy to stand that close to the reactor, wondering if you were receiving a dose of radiation that wouldn’t show up until many years later. More than the creepiness, there was a sense of awe at the people who put the reactor under the metal covering I could see. The metal shield looked old. Like plate armor laid over top of a building. It was called a sarcophagus I learned.

To our right was a new sarcophagus, shiny and arched, unlike the boxy original sarcophagus that had to be hastily applied while being exposed to tremendous amounts of radiation. I had learned in my obsessive reading before the trip that the sarcophagus I was looking at on reactor 4 was outdated—it should have been replaced years ago. It’s lifespan wasn’t rated for this long, but the project to build the replacement sarcophagus had stalled so many times that it was way behind schedule. It seemed like everyone knew the sarcophagus might collapse at any moment, but for some reason, trusted it wouldn’t. What would happen if it fell apart? How far reaching would the radioactive contamination be? The new sarcophagus still hasn’t been finished. There’s just not enough funding to get it done in a country too torn by corruption and civil unrest and invasions by foreign powers. They say they’ll get the new covering up in 2017 now…

We left briefly after arriving at the reactor, and headed toward the place everyone on the bus had seen before. The amusement park, the abandoned supermarket and shopping center, the wide empty concrete streets.

We walked around those places I’d seen in pictures, and the whole time there was a sense of being in some other world. Some future where the human race has fallen, and nature is slowly closing in to reclaim our strongest efforts to force shape and structure. I got my pictures of the iconic images that had been burned in my brain, and then I just stared. For a long time, in those places, I stared and let my imagination work. Not working to create some new post-apocalyptic plot, but to imagine what the place had once been like, and how it would eventually look. How time itself so quickly destroys what we so stubbornly work to create. How instantly and permanently nuclear power renders a place barren and destitute.

On the way out we passed a shopping center. I saw the buildings I recognized from so many photographs. The abandoned square, and the supermarkets long empty.

We stopped at Chernobyl on the way back for food. The radiation is low enough there, unlike Pripyat, to stay for extended periods of time. I wished I’d gotten more sleep, and that I’d had another day to explore. There really is no justifiable reason to go to that place. It was an impulse that drove me there, a fascination that had been built by so many things over the course of so many years, and that quickly it was already over.

I talked with some others about how amazing the trip had been and then, we drove back to Kiev. When I got back to my apartment and saw Pavo, he joked that I had survived. I could tell a lot of other people thought it wasn’t as cool as I did to go there. More stupid and perhaps insensitive even. I stared at my shoes and took them off, then all of my clothes, wondering what level of radiation had been embedded in them. It was very rare, they had told me, that someone breathed in a particle that an extremely high radiation content. I couldn’t think about that. I just had to get into the shower and then sleep. By then, late in the afternoon, my mind had turned to mush from lack of sleep. Sometimes when I’m writing I’ll think of that place. I loved my time spent living in Ukraine, and for me, the trip to Chernobyl was a once-in-a-lifetime event that had seemed so remote when I’d first searched from the comfort of my home in New Jersey about trips through the abandoned city. To be honest, if someone else provoked me, I’d go again in a heartbeat.